The Trouble With Sensible Project Names

Ever wondered why so many infamous projects have names that have absolutely nothing to do with the product the teams were working on? I always assumed it was intended to let the team members own part of the project at best, or an attempt by corporate to make things seem cool at worst.

I mean, who cares what the team name is? Everyone on the team knows they’re part of the project. The work performed by the team should standalone. The project will either be a success or a failure, but the name should be completely orthogonal.

It was thanks to this naive view that I picked the most boring, straight forward and dull project name when I put together a task force late last year.

The team was created with a single aim – given a technology’s test suite, achieve the performance target required for use in production. To make things more interesting, everything was running on KVM.

This was an experimental project, and we weren’t even sure that we could meet the target when we started out. What we realised pretty early on though was that the new team would need to include people from different areas. We created a cross-functional team, and a new team deserved a new name.

Naming things is hard. But I picked the most descriptive name I could think of. It was made up of the two major functional areas we’d be working on; the new technology and KVM. Let’s call it, the technology-KVM project.

This, it turns out, was a stupid idea.

Our goal was a very small piece of a much larger roadmap. As the R&D engineers, we had to understand whether it was possible to reach the performance target, which tunings were required and to write any patches to make that happen. Once we had the answers, the team would be disbanded and different engineers would pick up where we left off.

What I failed to realise was that only the team and a few stakeholders knew of this charter. The rest of the company had only a single way to learn about what we were doing: the team name.

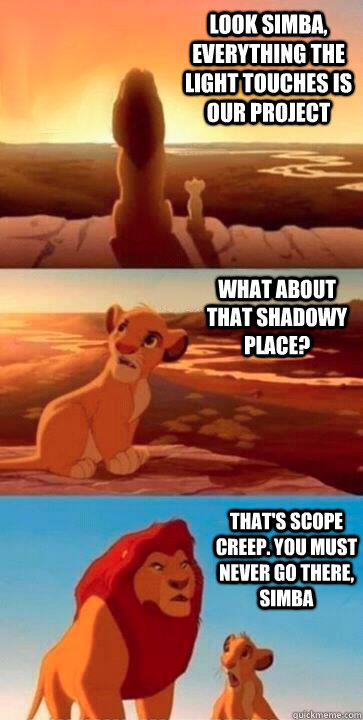

I spent a not insignificant part of my time explaining and re-explaining the team’s objective because everything even remotely related to “technology and KVM” was put on our plates. This included things far beyond the initial performance goal. We encountered scope creep like you would not believe.

There was also strong resistance to shutting down the team once we’d finished because people thought we wanted to somehow cancel the larger, company-wide project.

By using names and projects that people were already familiar with, I encouraged them to lump all semi-related tasks, ideas and problems into our team’s bucket. It’s actually a testament to the success of the team that we were so visible, which led to people wanting us to solve all “technology and KVM” problems.

None of this behaviour is surprising. It’s well established that humans love to categorise things. We deal with complex problems by organising and labelling objects, and building relationships in our minds. It’s how we make sense of the world.

Next time, I’m going to pick a name that is so abstract, so wacky, no one will have a clue what the team is working on. Using geographical locations seems to be quite popular.

Project God’s Own Country, perhaps?